Kohlenwäsche

Coal Washing Plant

Kohlenwäsche

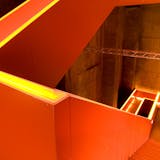

Anders als der Name es vermuten lässt, handelt es sich bei der Kohlenwäsche auf Schacht XII nicht um eine Waschanlage. Kohle lässt sich zermahlen, verbrennen, ja, verflüssigen, aber niemals reinigen. In den Steinkohlenzechen wurde ein pechschwarzes Kapitel geschrieben. Baulich sticht die Kohlenwäsche auf Zeche Zollverein heraus, sie ist nicht komplett von Backsteinfachwerk umhüllt. Mehr als 45 Meter hoch bietet sich auf dem Panoramadach ein beeindruckender Blick über das Ruhrgebiet. Man sieht die Kraft der Industrie, auf Landschaften der Arbeit, tiefer gelegt, aufgeschüttet, zergliedert und verblüffend grün. Hier ist es augenfällig, das Revier ist (wie der Klimawandel) – menschgemacht. Auch vom Menschen, von einem Architekten und Planer aus den Niederlanden, wurde die imposante Rolltreppe an der Kohlenwäsche entworfen: Dunkler „Pütt“ trifft auf leuchtendes Orange; nicht weil es Rem Kohlhaas’ Nationalfarbe ist, wie einige witzelten. Das Team aus Rotterdam wählte die Farbe als Kontrastmittel wie glühender Koks oder die flüssige Lava aus dem Erdinneren: unten und oben, ohnehin ein Leitthema im montanindustriellen Revier. Mit Blick auf die Arena des Fußballclubs Schalke 04 überbrückt die Rolltreppe 24 Höhenmeter ins Besucherzentrum Ruhr und damit dorthin, wo kaum ein Mensch zuvor gewesen. Die Kohlenwäsche war weniger ein Arbeitsplatz, sondern zuerst eine große Maschine. Nur wenige hatten Zutritt, nur wenige Menschen wurden benötigt. Sie kontrollierten die Maschinen, die das Fördergut separierten, klassierten und für den Weitertransport vorbereiteten. Der Lärm war ohrenbetäubend, die Luft von Staub gesättigt. Das unter Zollverein abgebaute Material wurde über Transportbänder der Kohlenwäsche zugeführt und in den Wasserbädern der Setzmaschinen sortiert. Selbst aus dem Kohlenstaub und dem Prozesswasser wurde noch brennwertige Kohle herausgefiltert. Schließlich gelangte das Material durch Trichter auf Bänder und Kohlenzüge. Die Kohlenwäsche stand auf Stelzen mitten auf einem imposanten Güterbahnhof. Die Gleise sind noch gut zu erkennen.

Coal Washing Plant

Contrary to what the name might suggest, the coal washing plant at Shaft XII is not just a washing plant. Coal can be crushed, burned and even liquefied, but never cleaned. A pitch-black chapter was written in the coal mines. The coal washing plant at Zollverein Coal Mine Industrial Complex stands out structurally as it is not completely encased with brickwork. More than 45 meters high, the panoramic roof offers an impressive view over the Ruhr area. One sees the power of the industry on landscapes of work, lowered, heaped up, dissected, and astonishingly green. Here it is obvious that the coalfield (like climate change) is man-made. The stately escalator at the coal washing plant was also designed by a man – an architect and planer from the Netherlands: the dark “mine” meets bright orange, not because it is Rem Kohlhaas’ ‘national color’, as some have joked. The team from Rotterdam chose the color as a contrasting medium like glowing cokes or the liquid lava from the earth’s interior: below and above, a key issue in the mining industry coal fields anyway. With a view of the Schalke 04 soccer club’s arena, the escalator bridges 24 meters in height into the Ruhr Visitor Center, and thus there, where hardly anyone has been before. The coal washing plant was not so much a workplace as foremost a large machine. Only a few people had access and only a few people were needed. They controlled the machines that separated, classified, and prepared material for further use. The noise was deafening and the air was saturated with dust. The material mined under Zollverein was fed into the coal washing plant via conveyor belts and sorted in the water of the water baths of the setting machines. Combustible coal was even filtered out of the coal dust and the process water. Finally, the material was fed through hoppers onto belts and coal trains. The coal washing plant stood on stilts in the middle of an imposing goods railway station. The tracks are still clearly visible.